Jake Berthot: The Enamels

April 2 - July 30, 2022

Curated by Geoffrey Dorfman

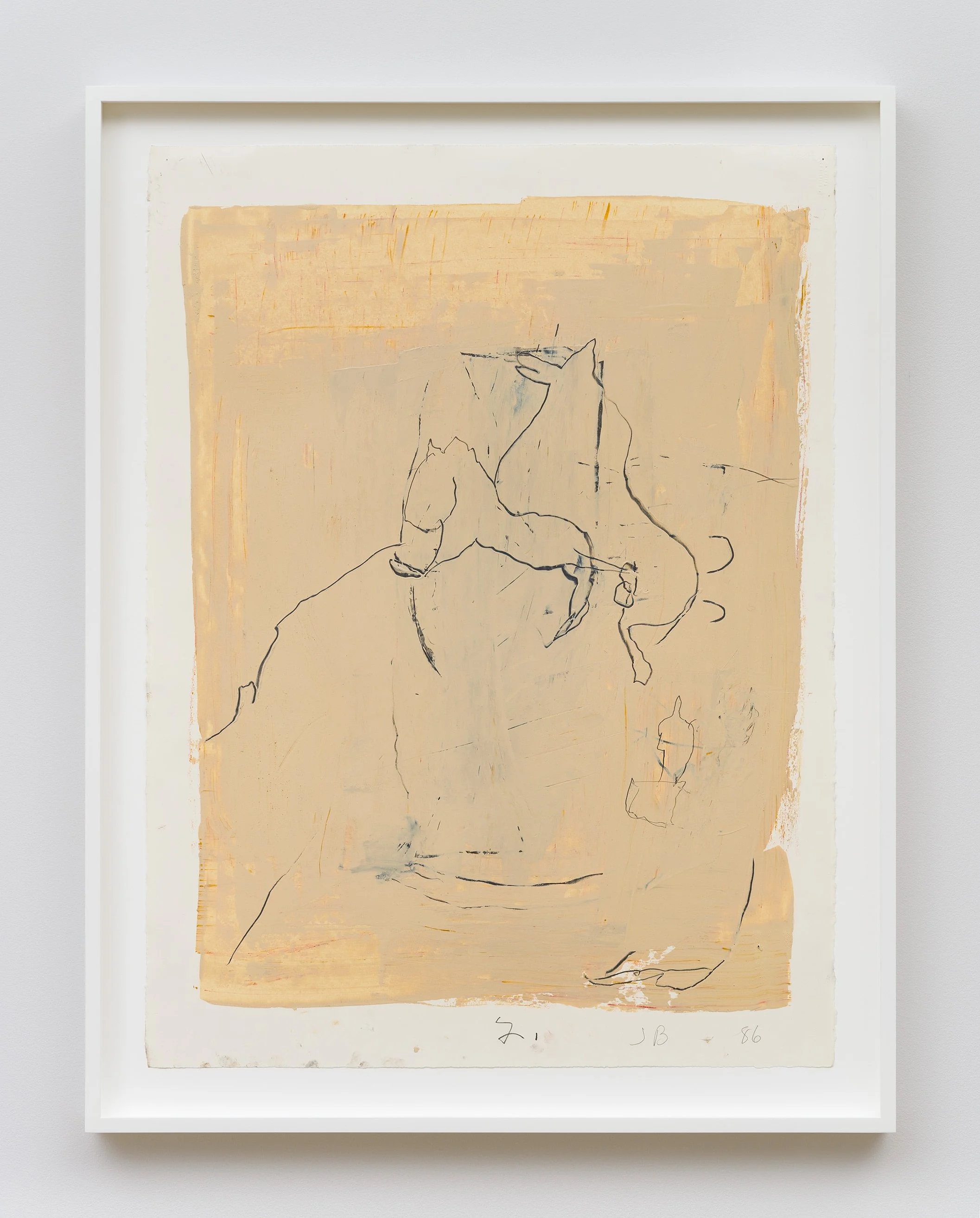

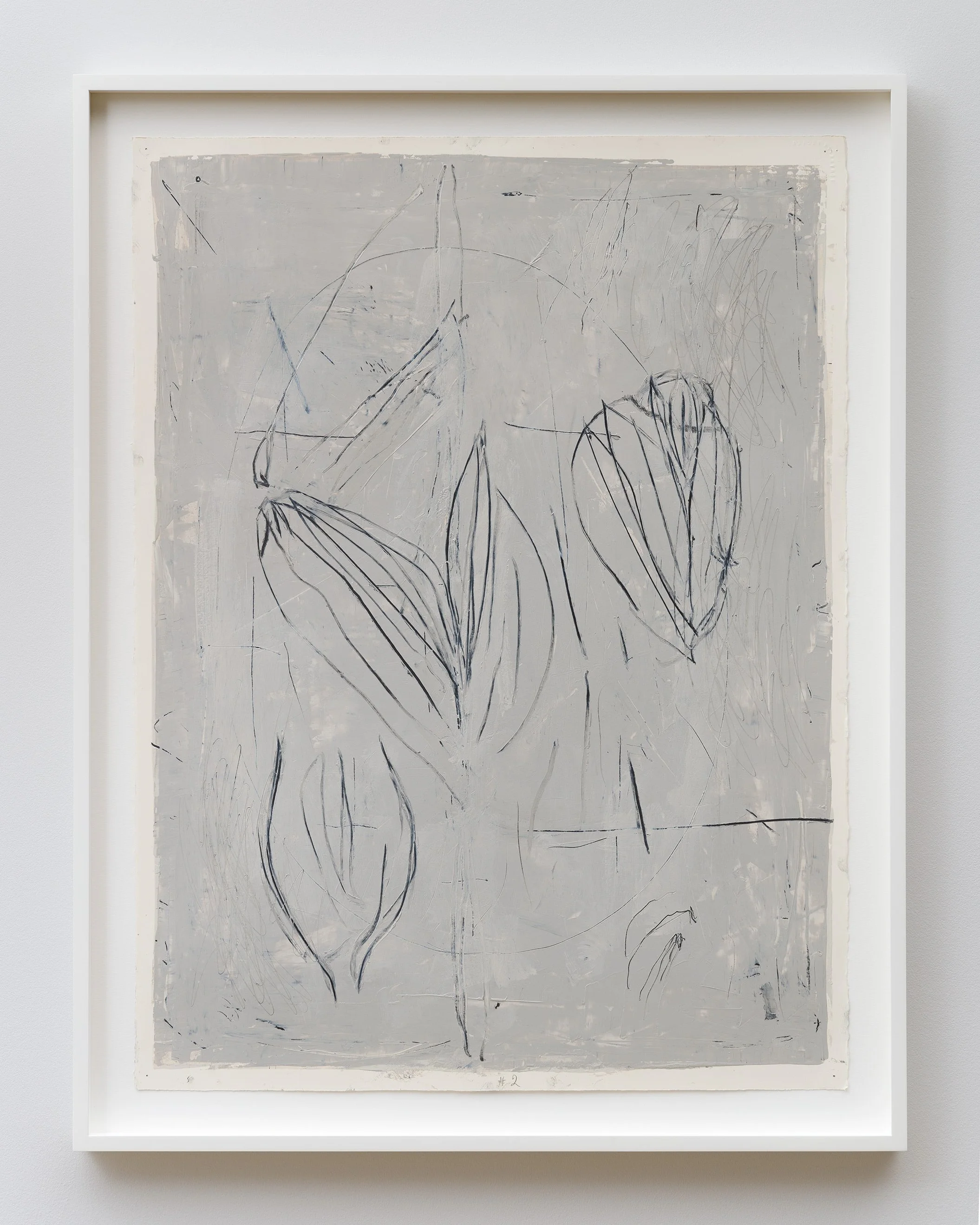

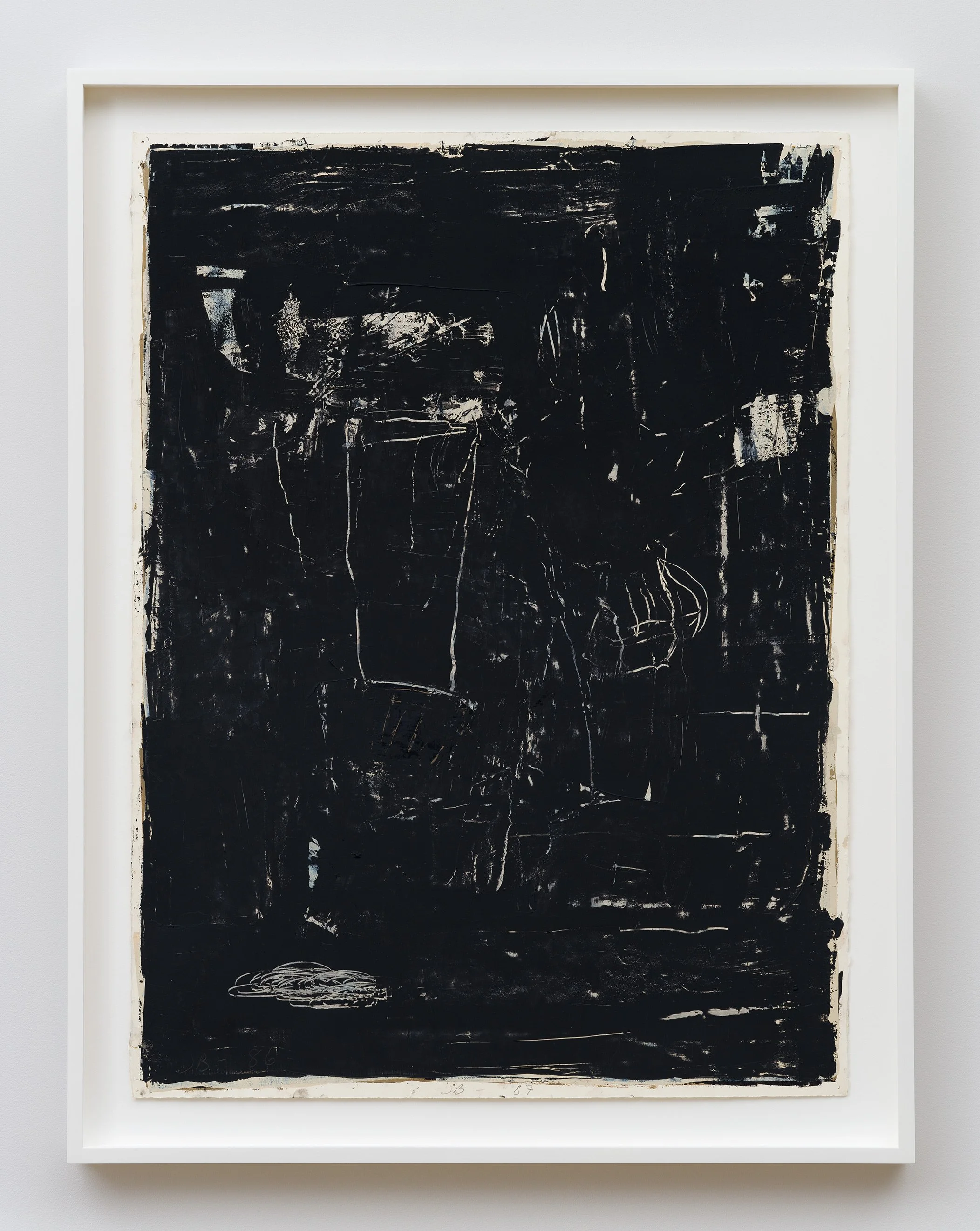

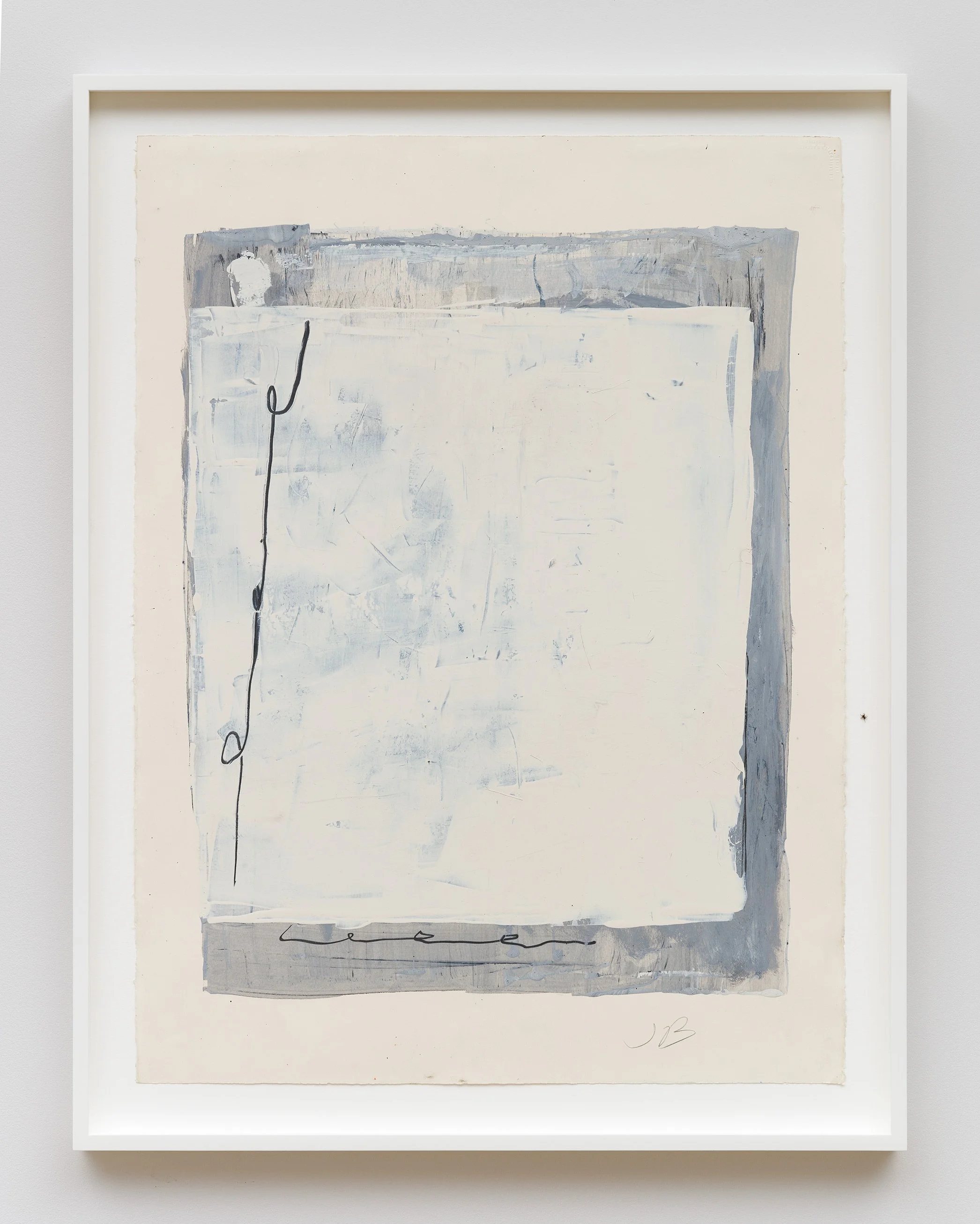

Jake Berthot

Untitled, undated

enamel on paper

30 x 22.5 inches

Courtesy the Estate of Jake Berthot and Betty Cuningham Gallery

There is joy in the sense of is it a drawing or

the source of its direction?That reasoning is so hard,

like opening a bureau drawer and piling whites on the bed,

whites doing all the wrong dance steps and lines

telling them where to go.— Michael Sickler, 2016

1

The Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation is especially pleased to offer the public an exhibition of Jake Berthot’s enamels on paper from the 1980s. Aside from the surpassing quality of these works, there is the additional welcome fillip of Berthot’s abiding relations with Milton Resnick. As Jake once put it — ‘Milton was my teacher…and like all great teachers he was a master…and like all great masters he carried a stick…he carried a big stick that — WHACK!…”It’s in the paint dummy”…”Where in the paint Milton?”...”Don’t be vulgar”

2

Jake Berthot was talking figuratively at Resnick’s memorial, as he apparently referenced the ‘zen slap’ tradition, in which enlightenment is received as an instantaneous shock, (in this case leavened subsequently with humor.) And it was at least in part due to this master/pupil relationship that Berthot invoked the notion of the art of painting, not so much as a profession but as a way of life: a mode of being. Art was to be less about perfecting a skill-set, than embarking on spiritual adventure.

Nonetheless Berthot realized by 1970 that Resnick’s notion of painting constituted a point of arrival rather than a place from which to begin, or build from. He soon moved on to constructed paintings, not entirely unrelated to the somber triptychs hanging in the Rothko chapel, but gradually the carpentry began to demand too much time and attention, and the quick drying acrylic paint — which boasted expediency but little else — proved ill suited to his meditative temperament. Above all a painter loves finely mulled oil paint, exploiting it, seeking what it might access in the realm of spirit. That sort of journey can fill up a life in a way that perfecting a skill-set cannot.

For some painters the art-historical seam between the Romanticism of the 19th century and the high Modernism of the last century has always been somewhat indeterminate. They could not ignore the impassive and timeless blanket with which nature erodes all that was once sharp, and irrepressibly corrodes and pits what was once smooth and mirrored. This realization alone can constitute between man and nature the kind of dialectic — solidity versus its dissolution — in which a painter, finding the right fulcrum point, can suspend himself. Consequently Berthot’s work has always hovered between geometry and the weather of sensation. He seemed to find a way to submit the intangibles — light, weather, and volume — to human deliberation. This took the form of a flexible scaffolding worked out beforehand on graph paper.

Different types of nets worked out on a grid had always been a feature of Berthot’s canvases, but the landscapes that issued from his move (in 1992) from downtown Manhattan to the woodlands of Accord in the Catskills of New York State, made what was previously implicit, explicit. Naturally, any verbal formulation like ‘weather affects volume,’ conjures up the forest and glade. The viewer can be forgiven for involuntary associations with late George Inness or the nocturnes of James McNeil Whistler, not to mention the ‘forests primeval’ of Longfellow and James Fenimore Cooper. Playing the role of heretic, Berthot was comfortable with the paradox that he was ‘advancing to the past.’ In a video in 2012 he declared he once more wished for the frame to act as a window.

Jake Berthot’s enamels on paper seem to deviate from this script. They are direct and quickly made, the compressed charcoal skidding and scratching through what must have been wet polished enamel in a spasmodic dance of the barely discernable. The viewer will find neither atmosphere, distance, nor a space inviting us to linger. The picture plane — be it black, white or unbleached titanium — is factic; a rolled-on skin that invites the scalpel. The outer coat does not receive the line — often almost a gash — passively but is disturbed, aroused to a judgment on the line’s veracity, and either leaves it be, adjusts it, or wipes it out altogether, leaving only trace elements.

For Berthot these works on paper were a chance to let his hair down, work informally, court chance, play, and come what may. These enamels can be said to function midway between painting and drawing. But we have earlier conjured up of the crepuscular atmosphere of Romanticism. Can we find such a connection in this frenetic sgrafitto?

I would argue that the key difference between the enamels and the rest of his oeuvre, is the illegible writing which is often situated next to the image. Berthot was, (and he shares this with Resnick,) a devotee of modernist and proto-modernist poetry. I don’t wish to get into literary expression itself — the play of the non-sequitur, dissonance, etc. — because Jake’s work remains resolutely visual. The multi-valence of most of his imagery and the accompanying asemic scribble which — entirely due to proximity — suggests a comment or an explanation, always verges on comprehension yet deliberately stops short. In the manner of the French Symbolists, Berthot refuses description. Disturbing the skin of the paint, his drawing remains primarily — not exclusively — a somewhat dissonant duet between line and surface. It quite simply cannot be read.

Yet the enamels do not entirely lie comfortably within the realm of abstraction. In some respects, one might initially be reminded of the anatomies in Leonardo’s notebooks, especially when skulls tended to appear in profile, such as appear in Berthot drawings now in the collection of MoMA or the Philips Collection. But it seems to have gone unnoticed that these particular skulls-in-profile appear to be immature, those of small children, in some cases distorted to the point of hydrocephalus. Coupled with the harried indecipherable scribble of his ‘descriptions,’ such images can’t help but allude to something horrific: the death of the child. Similarly the more abstract imagery also seems to court the instinctive alarm we feel in the presence of the nearly, but not quite, recognizable; body parts, copulating genitals, handless fingers, and various flotsam of all kinds, arrested in a suspension of glazy enamel.

What is a fit substitute for the time honored satisfactions of recognition? The erosion of memory, or suppressed experience? Time and again with these enamels, Berthot offers up chimera; meanings that can’t be fully grasped, either because they have been seemingly eroded by painterly circumstance — ie. the action of the brush — or suppressed because they were possibly unspeakable, even chilling. For all those French writers and poets — born and raised as Catholics on the far side of the Revolution — Satan was less of a villain, than the archetype of a rebel. And one suspects that the narcotic, fearful corners of the soul as described by Romantic poets like Gautier, Baudelaire, Lautreamont, and so many others, haunt Berthot’s pieces, as they did the Surrealists, and even later maudits like Artaud and Genet. Whether the enamel be black or white, the emotional tenor remains disquieting and even at times alarming.

A suggestive image that ultimately refuses the act of depiction — when generated by an artist of such quality — will nevertheless attain (or retain) its own reality. We could, for lack of a better word, call such an image, ‘abstract.’ But even so, it still speaks of something other than itself. There is always the presence of the ‘as if.’ The paradox of that sort of reality is that in this case its very elusiveness suggests — at least to this writer — the illicit and unspeakable. In the case of Berthot’s enamels such sensations make for an exceptionally potent visual art.

Geoffrey Dorfman

1 extracted from the poem, ‘Directions for Nothing,’ 2018. Michael Sickler is Professor Emeritus of Art and Art History, Syracuse University.

2 extracted from Jake Berthot’s tribute to Milton Resnick, in memoriam 2005.

All images courtesy the Estate of Jake Berthot and Betty Cuningham Gallery © 2022